Hamburgers and climate change: how do animal ag emissions stack up?

The hamburger has become central to national discussions about climate change, raising the question: how much does animal agriculture really contribute to greenhouse gas emissions? Photo source

On a recent visit to a late-night talk show, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez did something remarkable: the freshman Representative from the Bronx connected Americans’ appetite for hamburgers to climate change. “In the Green New Deal, what we talk about is –– it’s true –– that we need to take a look at factory farming, period,” she told the hosts of Desus & Mero. “It’s not to say you get rid of agriculture. It’s not to say we’re going to force everybody to go vegan or anything crazy like that. But it’s to say, listen, we’ve got to address factory farming. Maybe we shouldn’t be eating a hamburger for breakfast, lunch, and dinner.”

“Listen, we’ve got to address factory farming. Maybe we shouldn’t be eating a hamburger for breakfast, lunch, and dinner.”

Ocasio-Cortez’s hamburger comment inspired an immediate reaction from the right. At the Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC), Sebastian Gorka, former deputy assistant to President Trump, told the crowd that Green New Deal proponents “want to take away your hamburgers.” President Trump tweeted that the Green New Deal would “permanently eliminate” cows. Freshman Sen. Marsha Blackburn of Tennessee wrote in an op-ed that “if the Green New Dealers have their way, cows would be effectively banned over concern that livestock ‘emissions’ may contribute to global warming.” One columnist at The Washington Post wrote that the hamburger has become “the rallying cry for the GOP” against the Green New Deal.

While the hamburger comment and subsequent backlash made clearer that our food system ––often overlooked in discussions on climate change–– is a major source of global greenhouse gases, it also highlighted confusion about how much animal agriculture contributes to global warming. After all, estimates vary.

“Experts underestimate the climate impact of animal agriculture.”

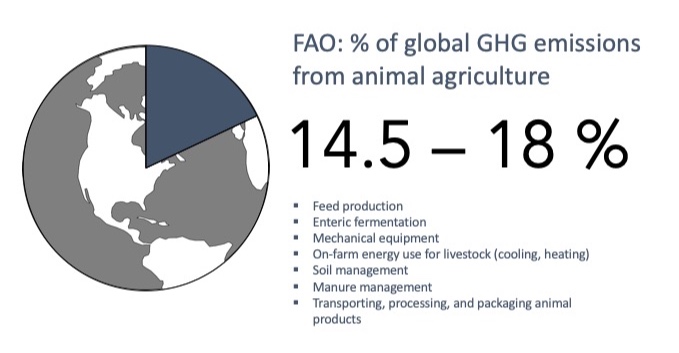

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has estimated that the agricultural sector contributes 9% of U.S. greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, with approximately 4% coming from livestock production alone. Globally, the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nation has estimated that the livestock sector contributes between 14.5% and 18% of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

Researchers Joseph Poore and Thomas Nemecek found a similar number in their peer-reviewed meta-analysis published in Science magazine. They estimated that the food chain is responsible for 26% of global GHG emissions, and animal products (including fish farms) account for 58% of these emissions, implying that animal products alone account for 15% of total global GHG emissions. Meanwhile, a 2009 report by the Worldwatch Institute found that livestock and their byproducts account for over 51% of global greenhouse gas emissions.

Making sense of this data can be difficult: why is there so much variety between national and global estimates and between sources? The confusion has contributed to our national failure to address the threat represented by animal agriculture. Former Energy Secretary Steven Chu is one of many leading scientists arguing that “experts underestimate the climate impact of animal agriculture.”

the challenge of evaluating a hamburger’s impact

Calculating emissions is a complicated process and estimates vary depending on what is included or excluded in the definition of animal agriculture, and how recent the statistics. Some sources only calculate emissions from “the farming part of agriculture,” such as enteric fermentation (methane from cows burping and passing gas), mechanical equipment, and manure management.

“Because food is a global commodity, what is consumed in one country can drive land use impacts in another.”

More comprehensive approaches, like that of FAO and Poore, include “upstream” and “downstream” contributions like animal feed production; transporting, processing, and packaging the animal products; and converting land from native ecosystems to land for animal agriculture. Poore et al. also includes emissions from aquaculture. The Worldwatch Institute goes even further, accounting for emissions from livestock respiration; the photosynthesis that is foregone by converting land for grazing; and processes like cooking meat, livestock waste disposal, and medical treatment for zoonotic illnesses and chronic diseases linked to the consumption of livestock products.

In addition to variation among methodologies, the interdependency of the global food system complicates emissions calculations. “Because food is a global commodity,” writes the World Resources Institute, “what is consumed in one country can drive land use impacts in another. For instance, with no change in productivity per hectare, a rise in beef demand in the United States (with beef demand in other countries held constant) could drive deforestation in Latin America to make way for additional pastureland.” Some sources may not take this interdependency into account, measuring only domestic changes, and thus produce a lower estimate.

“Let me say it again: agriculture and land-use generates more greenhouse gas emissions than power generation.”

Estimates of animal agriculture’s percent contribution towards total GHG emissions will also be lower in the U.S. than globally or in most other countries. This is because our overall greenhouse gas emissions are higher: the average American emits over 20 metric tons of CO2 equivalent per year, while the worldwide average is around 6 metric tons of CO2 equivalent per year. Almost two-thirds of our annual emissions come from power plants and transportation, two sources that are less prevalent in other countries and especially in the developing world. Thus, animal agriculture plays a proportionally smaller role in national emissions.

Animal ag is “at the top of the list” of climate challenges

This country’s added emissions from power plants and transportation should not distract from the critical role that addressing animal agriculture plays in mitigating climate change. In fact, Steven Chu puts animal agriculture “at the top of his list of climate challenges.”

In a lecture at the University of Chicago, Chu surveyed the world’s carbon-polluting industries and started with meat and dairy: "If cattle and dairy cows were a country, they would have more greenhouse gas emissions than the entire EU 28," he said. “Let me say it again: agriculture and land-use generates more greenhouse gas emissions than power generation.”

“Anyone can work towards reducing food waste and adopting plant-rich diets, two of the most powerful climate solutions at hand.”

Ultimately, while estimates of the climate impact of animal agriculture vary, the consensus is the same: minimizing our dependence on animal agriculture is a powerful tool to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and mitigate the effects of climate change on our communities.

In fact, Project Drawdown, an organization which researches and publishes data on the financial, social, and environmental impact of climate solutions, estimates that food sector solutions –– including both supply-side solutions (like agricultural production) and demand-side solutions (like diet, cooking, and food waste) –– could account for 30.6 percent of total emissions mitigation. This makes food the sector with the largest potential impact for climate change mitigation.

Paul Hawken, Co-Founder and Executive Director of Project Drawdown, summarized the food sector’s potential for climate change mitigation in this way: “Anyone can work towards reducing food waste and adopting plant-rich diets, two of the most powerful climate solutions at hand… Farmers, urban growers, backyard gardeners, and all of us eaters can, and will, lead the way."

And as Ocasio-Cortez pointed out, leading the way can start small –– as small as replacing your regular hamburger with a plant-based alternative.

how animal ag emissions stack up

When calculating the GHG emissions of animal agriculture, the EPA accounts for mechanical equipment, soil management, enteric fermentation, and manure management, but it does not include emissions from land-use conversion or the transportation, processing, packaging, and sale of agricultural products. The EPA has estimated that animal agriculture contributes 4% of U.S. GHG emissions.

The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nation has estimated that animal agriculture contributes between 14.5% and 18% of global GHG emissions. The FAO includes GHG emissions from feed production; enteric fermentation; on-farm mechanical equipment and energy use for livestock; soil and manure management; and transporting, processing, and packaging animal products.

In a June 2018 study published in Science, Poore et al. estimated that animal agriculture contributes 15% of global GHG emissions. This includes GHG emissions from feed production; enteric fermentation; on-farm mechanical equipment and energy use for livestock; soil and manure management; aquaculture; transporting, processing, packaging, and retail of animal products; and land-use conversion.

In its 2009 report, the Worldwatch Institute estimated that animal agriculture contributes over 51% of global GHG emissions. It accounted for emissions from livestock respiration; the photosynthesis that is foregone by converting land for grazing; fluorocarbons for cooling animal products; cooking meat; disposal of waste livestock products (bone, fat, etc.) and livestock liquid waste; the production, distribution, and disposal of livestock products and animal byproducts (like leather, feathers, skin, and fur) and their packaging; and carbon-intensive medical treatment for zoonotic illnesses and chronic degenerative illnesses linked to the consumption of livestock products. Finally, the Worldwatch Institute uses more updated (and therefore greater) estimates in its calculations for values like methane’s global warming potential (GWP) and the tonnage of livestock produced worldwide.

Project Drawdown estimates that implementing a range of supply-side and demand-side solutions within the food sector could eliminate 31.6% of global GHG emissions –– making food the sector with the largest potential impact.

Tia Schwab is a Stone Pier Press News Fellow and a senior at Stanford University, where she studies human biology with a concentration in food systems and public health.