Climate book clubs for kids are making a difference

Old Enough to Save The Planet written by Loll Kirby shares inspiring true stories about young environmental activists. (Illustration by Adelina Lirius)

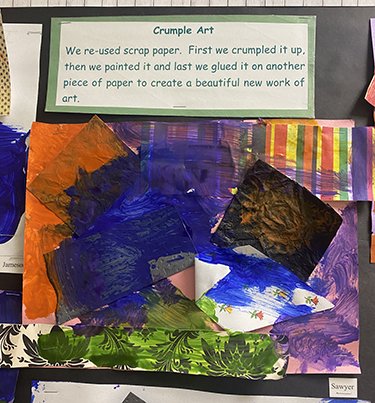

At the Risen Savior Lutheran Church School in Arizona, pre-k students are making art projects out of scrap paper, setting up recycling bins in their play areas, and coming up with ideas for building a school garden. Their teacher, Antonio Flores, says the students were inspired after reading the book Old Enough to Save The Planet. “The students wanted to feel the same way the characters in the book felt and they were inspired by their actions,” he says.

“We’re creating these spaces to talk about climate change but in a way that doesn’t contribute to more of that eco-anxiety that we hear a lot about. ”

Written by Loll Kirby and illustrated by Adelina Lirius, Old Enough to Save The Planet introduces 12 children from around the world who make a positive impact through environmental initiatives. One example is Adeline Tiffanie Suwana from Indonesia who combatted the flooding in her area by encouraging people to replant mangrove trees.

The book was featured by the American Public Health Association’s ECO Bookworms book club, which posts environmental book recommendations for kids on the second Tuesday of every month. As of 2022, the APHA decided to not just promote its book selections online but to also mail out free copies of favorite books to educators around the country, like Antonio Flores.

After reading Old Enough to Save the Planet, students reused scrap paper to create "crumple art” at Risen Savior Lutheran Church School in Arizona. (Photo Source: APHA)

I sat down recently with Evelyn Maldonado, the manager of ECO Bookworms, to learn more about the book club. The “ECO,” she explains, stands for “early climate optimists.” In keeping with the name, she tends to select books that promote messages of hope. The APHA supports the idea that by choosing the right books, approaching education in a developmentally appropriate way, and facilitating productive discussions, educators can help children become, yes, “early climate optimists” who are equipped to make positive changes in their communities and the world.

The New York Times also offers several kid friendly resources on climate change. Bad Future, Better Future is a simple introduction to the causes and effects of climate change with solutions and calls to action. (Illustration by Yuliya Parshina-Kottas)

“We want to make sure that with the Book Club, we're creating these spaces to talk about climate change, but in a way that doesn't contribute to more of that eco-anxiety that we hear a lot about–because climate change is scary,'' Maldonado says.

Children and future generations will be disproportionately affected by the impacts of climate change-related events. As the New York Times writes in its virtual children's book Bad Future, Better Future, “If you’re a kid, almost every year you’ve been alive has broken a temperature record or come close.”

While kids need to be aware of this future they are inheriting, the eco-anxiety that Maldonado referenced is also something to take seriously. Research indicates that feelings of grief and disempowerment can contribute to apathy and inaction towards climate change. So how do we approach the topic in a way that educates children without overwhelming them?

The APHA’s idea that children's books are a valuable tool for navigating this dilemma is well-founded. A “just the facts” approach to climate change education can cause distress among students ages 10 to 12 years old, according to research. In contrast, teaching that emphasizes opportunities for action fosters self-confidence and motivation. Children's literature and picture books have a unique ability to go beyond mere facts and incorporate new knowledge into captivating, character-driven stories.

A Kids Book About Climate Change is Maldonado’s favorite ECO Bookworms feature. Co-authors Zanagee Artis and Olivia Greenspan were already powerful climate activist in their teens. The book was published by A Kids Company About which also creates podcasts for caregivers and kids on climate justice.

But finding books suitable for children that engage with climate change in an inspiring way is no small task, even for highly motivated individuals like Maldonado. As the person in charge of book research, she often comes across books that are about climate change but don’t take care to underline messages of hope. Other times, she finds books that are about environmental issues but don’t explicitly discuss climate change. In those cases, facilitating productive discussions about the books is critical to staying true to the book club’s mission.

When ECO Bookworms featured Hurricane Watch by Melissa Stewart as its August 2022 pick, it included the questions “How do you think climate change is affecting natural disasters like hurricanes?” and “What are some ways you can prepare for extreme weather in your area?” Readers were encouraged to learn about the science of hurricanes and also reflect on why there might be more hurricanes in the future and how awareness and preparedness can make them feel less scary.

In addition to hope, diversity is another important criteria in the book selection process for ECO Bookworms. Studies have consistently found that communities of color are more likely to lack access to resources that can mitigate the effects of climate change, such as green spaces, clean water, and affordable renewable energy.

“We want to make sure that children see these books and they feel represented,” Maldonado says. “This climate movement is for everyone, but especially we want to bring light to the communities that are most burdened by climate change.”

“Grownups get really scared and then don’t want to do anything. We never want to do that to kids.”

Former teacher Corrie Locke-Hardy also understands the challenge of finding books that educate and empower students. In 2018, she started the popular account @thetinyactivist on Instagram to showcase meaningful reads for kids and help educators understand that social justice “is not as hard as they think it is.” Her Earth Day Roundup features a delightful selection of books that are informative and appropriate for a range of ages.

“Activism looks a lot of different ways,” Locke-Hardy says. It’s also about trusting the kids to understand what you're talking about and treating them with respect, she explains. “A lot of this stuff is scary, but also what will we benefit from scaring people? Grownups get really scared and then don't want to do anything. We never want to do that to kids.”

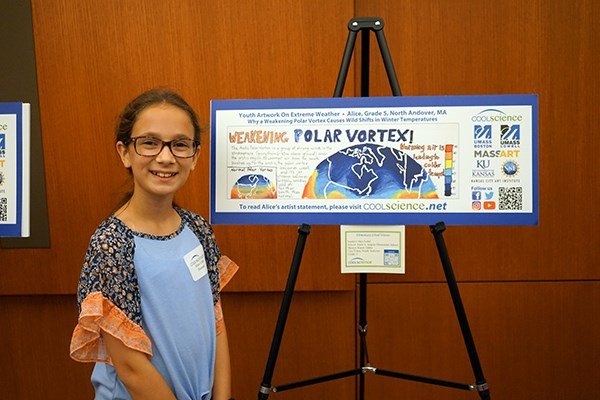

Alice Lobel shows off her winning artwork about polar vortexes. (photo source: Brooke Coupal)

It’s not always possible for kids to hit the streets in protest. But that doesn’t mean all we can do is remind them to turn the lights off when they leave a room. Even young children can write letters to representatives, volunteer at local environmental organizations, and start conversations about what can be done. As a winner of the 10th annual Cool Science Extreme Weather Art Competition, fifth grade student Alice Lobel displayed her artwork about the impact of climate change polar vortexes on city buses in the Merrimack Valley of Massachusetts. “I’m happy that other people are going to see it, and it can influence them to help stop climate change,” she says. At Powhatan Elementary School in Baltimore, fifth grade students are reading “Old Enough to Save the Planet,” and researching steps they can take locally to improve an environmental challenge.

Maldonado is optimistic about the trends she sees in new environmental children’s books that focus on equity, and she is fueled by the positive interactions she has with educators. “Seeing how parents and teachers are very excited and want to have these conversations with children, and the fact that we can help by putting these books out there and promoting them is very rewarding.”

Gabby Meerwarth is a Stone Pier Press News Fellow based in Claremont, CA.