Book review: Rebugging the Planet

Rebugging the Planet teaches us how vital bugs are to our environment, but it is not just an appreciation manual. It's a passionate appeal to protect bugs from climate change—because their loss will destroy us, too. (Photo source: Erik Karits via Wunderstock)

When I was in preschool, my whole class spent recess time out in the dirt next to the playground, digging for earthworms. It was a competitive game.

We tallied our worms and got bonus points for bigger specimens, but ultimately, all of our worms ended up in the same bucket, and they were all returned to the same dirt. Our worm hunts were completely self-directed—our teachers never asked us to spend our recesses like that. They just encouraged our curiosity, and made sure we washed our hands afterwards.

And yet, only a few years later, when a friend of mine picked up an earthworm with her bare hands and offered it to me, I refused, not wanting to touch it. I was struck even then—somewhere between the ages of four and seven—that worms had become gross, without my ever realizing it.

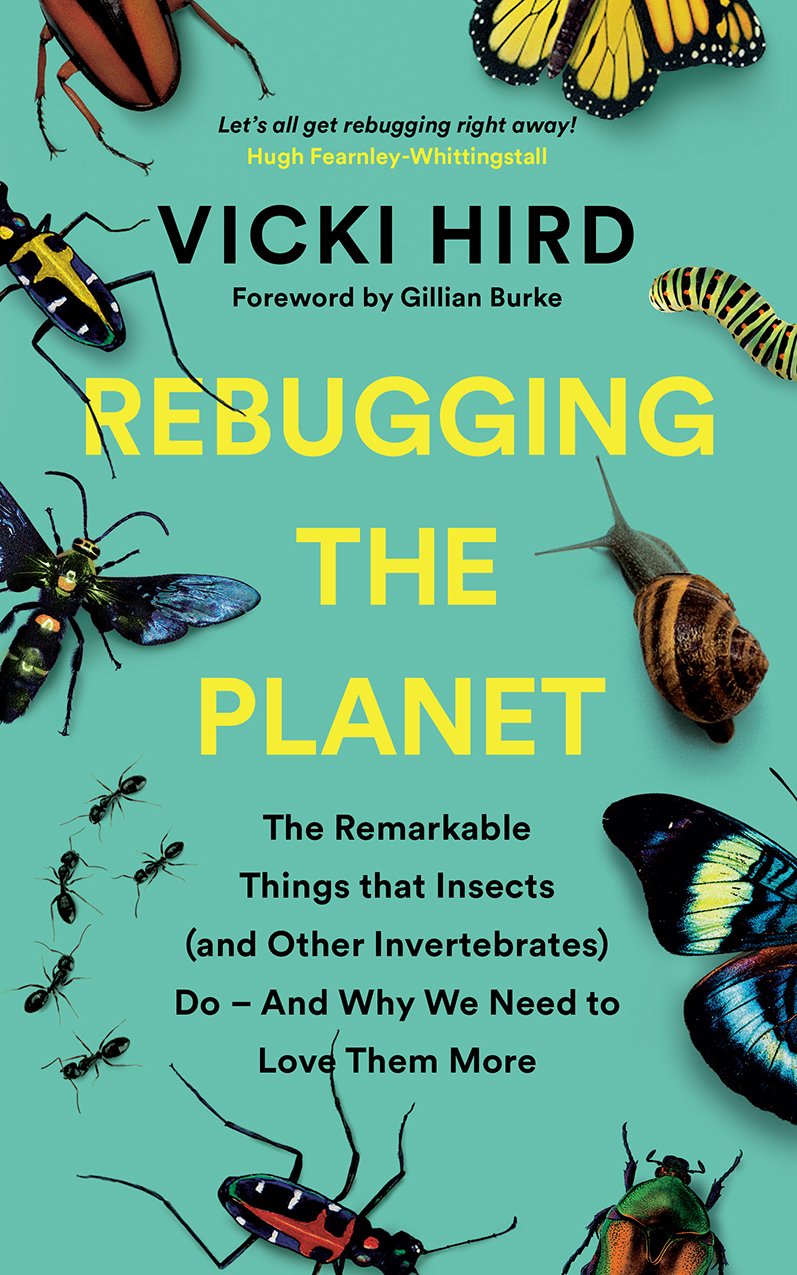

The simple truth is that many of us are conditioned to fear and hate bugs as we get older. We think of bugs as signs of dirtiness, as garden pests, or as threats that can bite and sting us. As author Vicki Hird writes in Rebugging the Planet: The Remarkable Things that Insects (and other Invertebrates) Do—And Why We Need to Love Them More, this is an attitude we ought to change.

Hird is an award-winning environmental campaigner, writer, researcher, and strategist—as well as a self-proclaimed “bug obsessive.” Rebugging the Planet is not just an insect-appreciation manual. It is a passionate, timely argument composed of three parts. First, that bugs are vitally important to humans and deserve our appreciation. Second, that bug populations are in decline due to climate change. And finally, that humans need to band together to protect them. It’s an argument that flows logically, but feels tangential when placed in the wider context of combating climate change. More on that later.

So how are bugs vital to human life?

“We take bugs for granted, and our impact on our shared environment has been detrimental to our tiny neighbors. ”

Hird has a long list of reasons. Bugs are key pollinators. A third of our food crops are pollinated by invertebrates, which is cheaper and easier than manually pollinating with brushes or “robo-bees.” Other pollinators, like wasps and ladybugs, also help control pest species like flies, aphids, and slugs.

In the ground, invertebrate bodies comprise much of the organic material in soil. Beetles and worms are great custodians and recyclers, turning waste and carrion into fertilizer. Worms, like the microscopic rotifer, are also crucial to many of our water treatment systems, helping to break down waste and increase oxygen. Without bugs under the earth and in the air, we would be hard pressed to grow food or fibers. And, of course, bugs are vital food sources for animals higher up in the food chain.

Yet, we take bugs for granted, and our impact on our shared environment has been detrimental to our tiny neighbors. Insect populations around the world are declining, with one 2019 study predicting that more than 40 percent of species are at risk of extinction in the coming decades—more than double that of vertebrate species.

A misconception many of us hold about bugs is that they’re very hardy—capable of ingesting toxic chemicals and living where other animals cannot. And while it is true that invertebrates as a whole are unlikely to go extinct, we cannot forget that their size makes them vulnerable to environmental changes.

Among the leading causes of the so-called “Insectageddon”: extreme temperature shifts, pesticide and fertilizer pollution, and light and noise pollution. Even 5G wireless signals have been observed to cause some insects to overheat and change behaviors, Hird writes. And it’s not just insects that are suffering. Earthworms, for example, are in danger partly because they need moisture to survive—moisture that is inhibited by drought and intensive farming.

Earthworms improve soil health by digging tunnels to hold moisture, increasing carbon, and supplying nutrients—which can raise crop yields by a quarter. (Photo source: Karolina Grabowska via Pexels)

So what can we do to help? Hird has a lot of ideas. Taking cues from the rewilding movement—an approach to conservation that attempts to recreate the earth’s natural ecological systems—Hird recommends rebugging. While rewilding projects tend to benefit large tracts of land and large predators like wolves, Hird proposes rebugging as a smaller scale practice that can be done from home—quite literally.

“…we need to find new ways to live while reconnecting with the ecosystems we live in, creating a richer world in which people and nature can thrive together.”

A key component of rebugging is that it happens in human spaces—like houses, parks, and cities—in contrast to rewilding projects, which tend to take place in isolated preserves. Hird argues that, as valuable as rewilding is, conservation should not always prioritize removing human impact. Humans are part of nature, after all, and we should be conscious of our spaces as also being important natural ecosystems that deserve our attention and protection. As Hird writes, “…we need to find new ways to live while reconnecting with the ecosystems we live in, creating a richer world in which people and nature can thrive together.”

Rebugging can take numerous forms, but they fall into two main categories. The first centers on small, individual actions—easy steps, like not killing bugs, avoiding using pesticides, and leaving your outdoor spaces a bit messy so that bugs can feed on weeds and decaying wood. If you’re looking to go a bit further, Hird also recommends planting wildflowers, switching to biodegradable cleaning products, reducing food waste, and avoiding buying plastic-based textiles.

In truth, nearly half of her suggestions are actions that many environmentally-conscious people are already doing—like buying local, organic produce, reducing emissions, and recycling. But Hird makes it clear that individual actions are not enough, so the second category of rebugging stresses the importance of collective organizing and policy change.

What the planet and the bugs need, more than a few more dead logs and wildflowers, is for laws to be passed internationally to curb industrial pollution, dismantle factory farming, protect the remaining wild landscapes, and so on. Again, these are policies many environmentally-conscious people want anyway, but have been largely denied by politicians beholden to corporate interests and lobbying groups.

The frustrating part of Hird’s call to action is the fact that it is already an uphill battle fighting for these policies for the sake of the lives of humans. So how can we possibly expect better results when fighting for the sake of bugs?

“If we want to save the bugs, we have to get other people to care about them, and that requires spreading bug positivity. ”

My takeaway here is conflicted. On one end, rebugging aligns very cleanly with my current efforts to “go green.” However, I was already recycling, eating organic, and shopping sustainably for the sake of the planet at large and for other human beings, so being told that I should be doing it all for bugs feels tangential and redundant.

That is not to say that Hird’s entire argument is unnecessary. Her first points—that bugs are essential and deserve appreciation and consideration—still feel important. Even if I cannot bring myself to campaign to save the planet for the sake of bugs, I can care about them. That attitude change is, in truth, the biggest adjustment that rebugging demands. If we want to save the bugs, we have to get other people to care about them, and that requires spreading bug positivity.

It means changing our own visceral reactions to bugs and challenging our collective presumptions about bugs. It also means reconfiguring how we live with them, and learning to look at our spaces differently. We do not need our houses and yards to be sterile and bug-free. Perhaps most importantly, bug positivity can be instilled in future generations, so that young children never internalize the assumption that bugs are gross, like I once did.

It’s not easy to overcome social programming—I actually swatted a bug that landed on my laptop screen while writing this review—but it’s worth the effort. For the sake of our planet, we need to love the bugs that keep it clean and pollinated. Plus, we could all do with a little more enthusiasm in our lives. My days of digging for worms with gusto may be behind me, but I have many days of rescuing spiders and feeding butterflies ahead.