‘Kiss the Ground’ review: So, the soil may save us. Now what?

Farmers, scientists, cows, and celebrities work together in this documentary to spread the good word about regenerative agriculture and its potential to mitigate climate change. The message gets across, but the film downplays a meaningful call to action. (Source: Kiss the Ground)

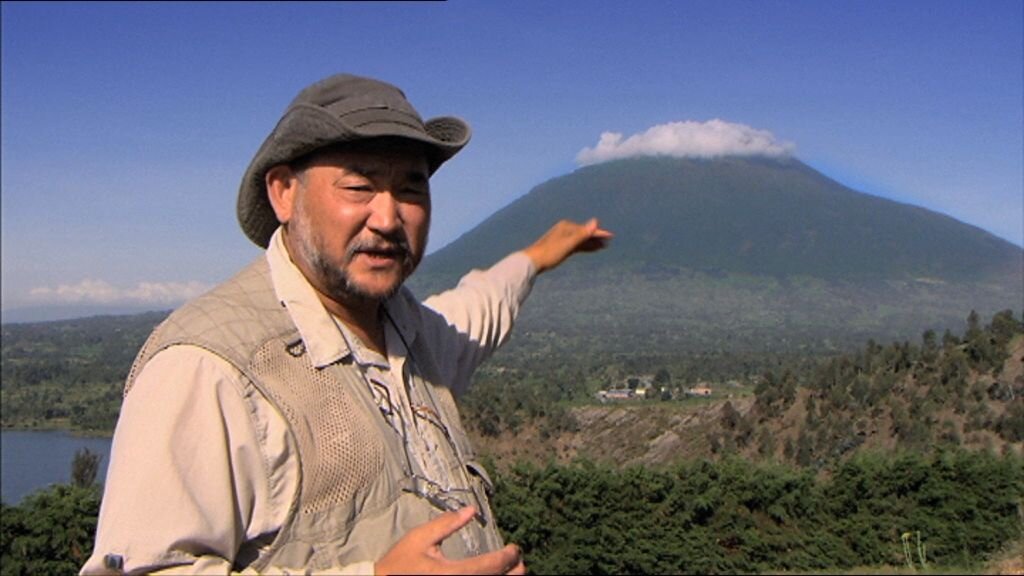

Here’s the big picture: a wide-screen projection of the surface of the Earth. Overlaying it, a swirling heat map of global atmospheric carbon, changing from dark red to cool blue over the course of a year. Watching attentively, a classroom full of farmers.

Ray Archuleta, previously a conservation agronomist with the Natural Resources Conservation Service and the co-founder of the Soil Health Academy, stands at the front talking to the farmers, and to us. In March and April, he says, farmers are tilling. Plowing the earth, preparing fields for planting, exposing bare soil. Water and carbon escape into the atmosphere in enormous plumes blanketing the entire northern hemisphere—shown onscreen as ominous swirls of red. But as crops grow month by month, drawing down atmospheric carbon, the red is gradually replaced by greens and then by blues, until the map is recognizable once again as the pale blue dot we call home.

“Save our soil in hopes the soil might just save us.”

This is the central statement of Kiss the Ground, an eco-educational Netflix documentary directed and produced by Josh and Rebecca Tickell. On-the-ground agricultural practices carried out by millions of individual farmers directly affect the health of the soil, and by extension, global atmospheric carbon levels and the pace of climate change. By practicing regenerative agriculture, a no-till, chemical-free system designed to bolster and protect soil health, we can grow healthier plants, sequester more carbon, and ultimately “reverse climate change.”

Narrator Woody Harrelson calls regenerative agriculture “a simple solution—a way to heal our planet” and asks viewers to “save our soil in hopes the soil might just save us.”

The short version: Growing food with regenerative agriculture leads to healthier soil, better food, cleaner skies, and clearer water. Watch the film trailer here and the full movie on Netflix. (Source: Kiss the Ground)

The evidence for this claim is research-based, clearly communicated, and visually supported with animations that illustrate submicroscopic events like carbon cycling and expansive drone shots for grand reveals, like the actual desert plateau that is turned back into rolling green farmland. Celebrity activists, including Ian Somerhalder and Patricia Arquette, drop by to promote a suite of carbon-capture climate change solutions they’re personally involved in, from diversified permaculture to compost toilets.

“It’s a good vibe, like a 90-minute team-taught TED Talk.”

While the film can at times feel like a jumble of connected concepts and issues with an occasional celebrity cameo, the documentary is overall optimistic. It’s filled with intelligent people who refuse to shy away from the impending climate cataclysm and have instead dedicated themselves to the daily work of facing it—as farmers, educators, scientists, and yes, even as politicians. It’s a good vibe, like a 90-minute team-taught TED Talk—industrious, sensible, leaning into the future.

I approached this film with professional interest, not just as a News Fellow with Stone Pier Press, but as someone trained in biology at college, regenerative farming at the Rodale Institute (three of the film’s agricultural experts work/ed here), and food systems at graduate school.

The movie is preaching to the choir here, which I think is why I found it disappointing that the filmmakers felt the need to wrap perfectly good explanations of the mechanisms of carbon sequestration and climate change in more evocative but nebulous language like "heal the planet" or "save the soil.” The evidence in favor of regenerative agriculture is irrefutable. I honestly thought it would stand on its own.

Repeatedly using abstractions to sum up complex issues makes people comfortable talking about soil as if there is one entity, “soil,” that we (who is we, anyway?) can scoop up and heroically rescue. “Heal the planet” is a phrase that implies not only the existence of some kind of natural balance to which we can return, but the existence of a cure that human benevolence can deliver.

To me, it undermines the articulate, informative explanations offered by the professionals with actual working farms and advanced degrees who are given the floor for much of the film. Their technical expertise should be enough to convince us that their message is not only correct but worth listening to. It’s the same reason we don’t call doctors “healers” anymore—their body of knowledge has been formalized, their work recognized and legitimized as a profession, and their value become obvious.

Industrial agriculture (left) causes desertification through tilling and synthetic pesticides and fertilizers. Regenerative agriculture is a more resilient system based on principles of soil health and biodiversity that integrates multiple crops, cover crops, and livestock animals. (Source: Maggie Eileen Lochtenberg, freelance artist and transformational witch. Instagram @maggie.eileen.art)

We’re trapped on a planet to which we've already done irreparable damage. Humans have created such a massive disturbance in our topsoil and atmosphere that the only way out is forward. Rousing speeches have their place in communicating the gravity of the situation to the public, funders, and policymakers, but it’s not a framing that suggests concrete action, or even a plan. If filmmakers are serious about educating and calling people to action, they shouldn't couch their messages in gentle, sweeping language. There’s no sense in wasting a precious resource like attention by skirting the truth that transitioning to regenerative agriculture, or changing any entrenched industrial-economic system, is a lot of work.

“As someone who has farmed using diesel tractors and bare hands, I can tell you regenerative agriculture isn’t the solution to a greener future. It’s a tool.”

As someone who has farmed using diesel tractors and bare hands, I can tell you that regenerative agriculture isn't a “key” or secret or the single solution to a greener future. It's a tool. It’s a practice that requires a level of care you have to commit to every time you go into the field. It’s a system of thinking and working that takes knowledge, skill, experience, endurance, affinity, if you've got it, and a lot of hard work, just like any other difficult undertaking.

With this in mind, I feel obliged to point out the uncomfortable contrast between the two main types of interviewees in the film. Half are experts working in their respective fields, and the rest are celebrity activists for whom regenerative agriculture and climate change is more or less a cause.

On one hand, the use of celebrity ambassadors is an unsubtle but effective tactic to draw casual viewers and followers. It is a strategic use of fame and visibility, and the filmmakers and stars are clearly aware of the cultural impact of their appearances in the film. Stardom is a complicated thing, but at least all that money and power are being put to good use.

Still, it’s hard to ignore that the filmmakers featured almost exclusively rich, white American celebrities in a film about global systems change released in the middle of a national reckoning about our ability to be a diverse and equitable society. I’m not saying the filmmakers should have gotten a token Black person, but they couldn’t have gone wrong centering the voices of people for whom the stakes of not reversing climate change are much higher than their own. After all, it’s communities of color, low-income communities, and immigrant communities who do the majority of the essential work of growing food and yet are most exploited and harmed by the agroindustrial complex.

The movie didn't even include an indictment of current US politics or President Trump, which is notable by its absence considering the film was released so close to election time. Tying the message of Kiss the Ground to voting for policymakers who will systemically change the way the country incentivizes regenerative agriculture and reversing climate change would have been an obvious and easy leap to make. (PLEASE VOTE November 3rd or earlier!! I promise it’s way easier to mail one ballot than to cut meat out of your diet or petition your city to collect compost!)

From rehabilitating entire ecosystems to growing home victory gardens, there are plenty of ways to get involved in regenerative agriculture.

So why did a documentary about regenerative agriculture and the power of growing plants not encourage people to grow their own food? To start tiny or full-size victory gardens, turn their lawns into meadows, petition their city councils to zone land for community farms/gardens, or donate to conservation nonprofits or farmland trusts? Suggestions for viewers to compost and eat a plant-based diet come off as both insignificant and off the mark after the grand scheme of carbon cycling via production agriculture the whole film had been setting up. (Though they’re still good ideas.)

There was a huge opportunity for the filmmakers to ask open-ended questions and seek new avenues of thought and action, but they went the safe route of trying to be inspiring. It’s not a bad thing per se. It’s absolutely good to love the earth and want to save the soil. But I wish people with platforms like documentary films or acting stardom would start framing issues with words that suggest physical work, like "repair" or “fix” or even "care for/take care of" (i.e. care as a social process). We need to talk about agriculture in a way that’s meaningful to people with boots on the ground and enumerate specific steps that lead to material change.

“There was a huge opportunity for filmmakers to seek new avenues of thought and action, but they went the safe route of trying to be inspiring. ”

Farm work is unglamorous, underappreciated, and not very well-paid for the most part, but it just so happens to be crucial to the survival of our species. To move the conversation forward with the urgency this topic deserves, filmmakers have to use the emotion they elicit to generate willpower and give the public the conceptual framework they need to act, not just to feel.

Francis Ge is News Fellow at Stone Pier Press and an aspiring first-generation regenerative farmer.