How animals lost out to humans

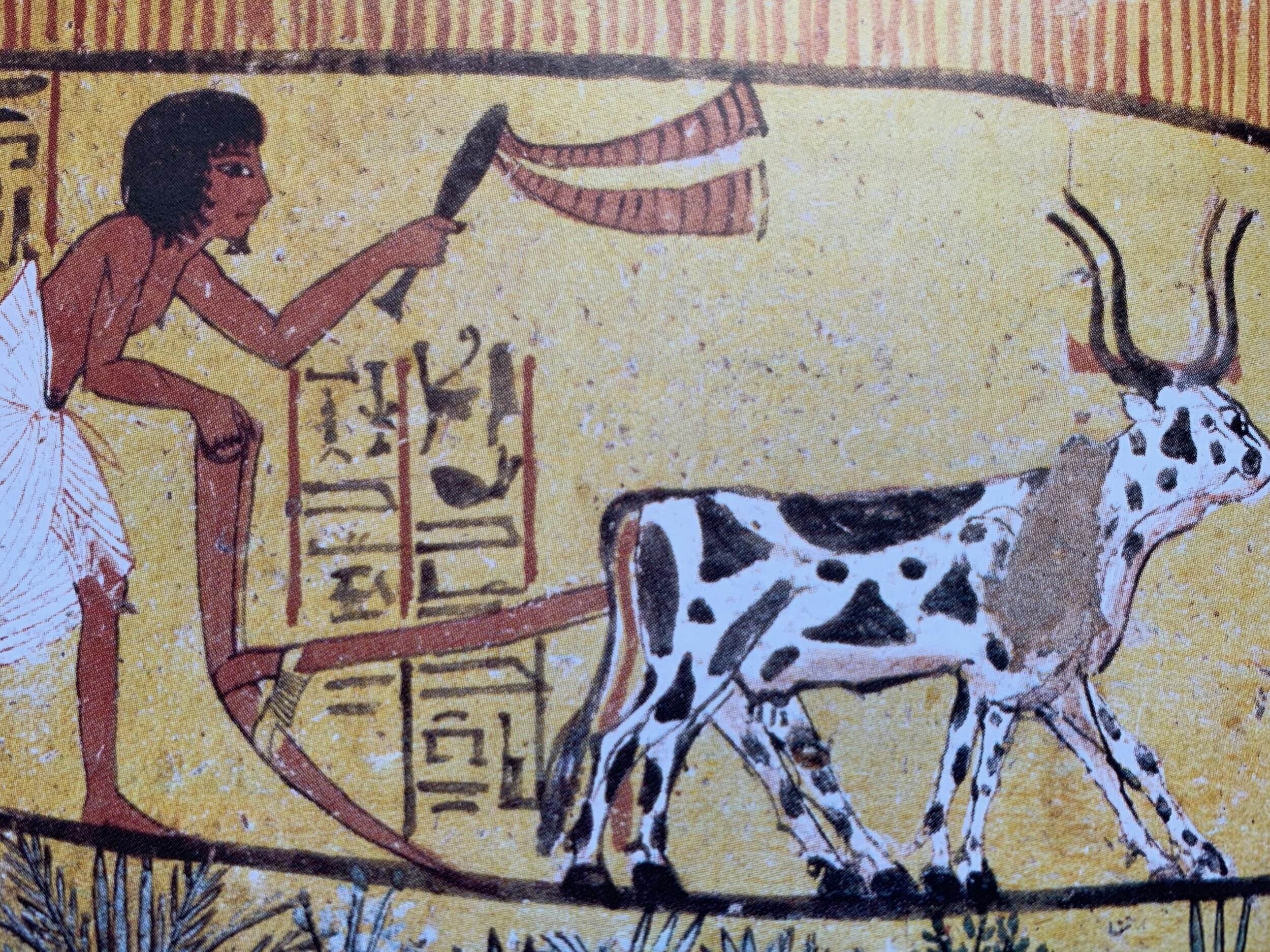

Humans began dominating animals after weaving narratives that gave us the upperhand, argues author Yusef Harari in his book Sapiens: The History of Humankind. Image: Visual/Corbis, from Sapiens.

Sometimes you just have to add fuel to the existential fire. As we all struggle to hold onto what's recognizable in a contemporary world transformed by the coronavirus pandemic, I decided to “shelter-in-place” with the engrossing but disquieting recent bestseller, Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind.

“...modern industrial agriculture might well be the greatest crime in history.”

Sapiens author Yuval Noah Hariri, an historian and philosopher who has garnered accolades from Barack Obama and Mark Zuckerberg, weaves an astute, vivid tale about the rise of humans from “an animal of no significance,” to the omnipotence of an “animal that became a god,” to an uncertain future in which the “end of Homo sapiens” may be near. With an equal measure of insight and compassion, Harari also kindles an understanding of the increasingly catastrophic impact we have had on the species around us over the millennia, concluding that our treatment of farm animals “might well be the greatest crime in history.”

Animals lost out to human “fictions”

Harari attributes our growing dominance over other animals to a surprising factor: our capacity to create what he calls fictions, or shared narratives, that facilitate mutual trust and cooperation. Take, for example, money. Whether paper bills, bank accounts or bitcoin, money “isn’t a material reality – it is a psychological construct,” and only has value so long as we believe it does. Harari persuades us that the same is true for religion, politics, economics, and all human systems, and that the human capacity to dwell in these fictions has made all the difference.

From our earliest days as “wandering bands of storytelling Sapiens” and especially at the key junctures of the Cognitive Revolution (a term Harari coins to describe the dawn of societal fictions about 70,000 years ago), the Agricultural Revolution (12,000 years ago), and the Industrial Revolution (beginning a mere 250 years ago), human societies have increasingly sidelined the animals who have had the misfortune of evolving alongside our fictions.

Beginning with the Cognitive Revolution, our nomadic ancestors left mass extinctions in their wake as they spread across the globe. They used primitive weapons but superior teamwork to permanently vanquish entire species of sci-fi-sounding mega-fauna like two-ton armadillos, giant ground sloths, and ten-foot-tall elephant birds. Harari rounds up a record that “makes Homo sapiens look like an ecological serial killer.”

Giant sloths and armadillos were some of the earliest victims of human fictions. Image: Waterhouse Hawkins c 1862, from Sapiens.

Even so, the animist outlook of hunter-gatherer societies granted other animals equal existential footing. “The fact that man hunted sheep did not make sheep inferior to man,” writes Harari, “just as the fact that tigers hunted man did not make man inferior to tigers…[all] beings negotiated the rules governing their shared habitat.”

“The domestication of animals was founded on a series of brutal practices that only became crueler with the passing of the centuries.”

The earliest farmers created different stories, developing theist beliefs that demoted “plants and animals from equal members of a spiritual round table into property.” Humans, made in the image of gods, now mattered more than other species. Dubbing the Agricultural Revolution “history’s biggest fraud,” Harari describes a “Faustian” bargain that found farmers trading long, hard hours in the fields for the prospect of a full granary. But domesticated animals got an even worse deal:

from a narrow evolutionary perspective, which measures success by the number of DNA copies, the Agricultural Revolution was a wonderful boon for chickens, cattle, pigs and sheep…[but this perspective ignores] individual suffering and happiness. Domesticated chickens and cattle…[are] among the most miserable creatures that ever lived. The domestication of animals was founded on a series of brutal practices that only became crueler with the passing of the centuries."

A factory farmed calf, kept in a tiny cage separate from her mother. Image: Anonymous for Animal Rights, Israel, from Sapiens.

After those many centuries, the Industrial Revolution rewrote the narrative yet again. Harari details the variety of horrors faced every day by mass-produced animals, designated as “cogs in a giant production line.” But in a twist of irony, the same science designing our oppressive factory farms is revealing “that mammals and birds have a complex sensory and emotional make-up,” and that treating living creatures like machines causes them physical, social and psychological stress. We also know that factory farms are bad for human health, and have been associated with other recent epidemics, like swine flu.

enslaved by industrial agriculture

Harari doesn’t mince words when he compares the modern animal industry to the Atlantic slave trade, casting both as stories of indifference rather than hatred. Just as slavery was the open secret fueling the economy of colonial America and imperial England, today we collectively look the other way as industrial agriculture enables a shrinking number of farmers (currently 2 per cent of the US population) to feed a growing number of people, now free to become doctors, construction workers, or Silicon Valley engineers.

Chicks on a conveyor belt in an industrial chicken hatchery. Image: Anonymous for Animal Rights, Israel, from Sapiens.

Looking back, Harari concludes that we can pat ourselves on the back for our human accomplishments only if we ignore the fate of other animals. “Much of the vaunted material wealth that shields us from disease and famine was accumulated at the expense of laboratory monkeys, dairy cows, and conveyer-belt chickens.”

Looking forward, Harari imagines many possible futures in which humankind will once again join the ranks of the “animals of no significance,” superceded by artificial intelligence, cyborgs, and other novel beings. We can only wonder how karma might play out for us.

saved by a new storyline?

Sapiens tells a disconcerting non-fiction tale about the primacy of human fiction. But in its truth-telling, it opens up new potential storylines. We have the power to reimagine our institutions, economies, biases, and preferences, to transcend our anthropocentric focus. If culture itself is fundamentally a “network of artificial instincts” fueled by collective fictions, we can nurture a more compassionate set of instincts about how we feed ourselves, which may take a variety of forms. Deciding which animals have significance is all about the story, and the storyteller.

Just now, COVID-19 is laying bare the fictions of our daily lives, at least temporarily. Harari, a vegan himself, makes me believe that we can write a new story for ourselves, and for the animals who cohabit our planet, and for our planet itself, if we can find a way to harness the immense power of our collective imagination before our time is up.

Susan Miller-Davis is a Stone Pier Press News Fellow and Principal of Infinite Table, based in the Bay Area.