An ocean farmer dreams big, for all of us

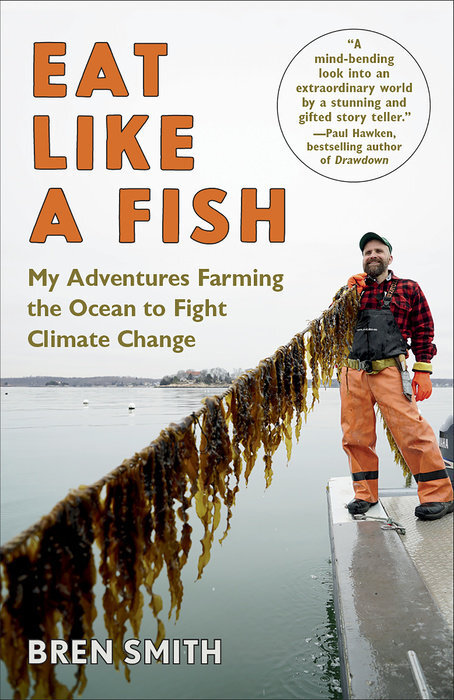

Bren Smith’s vision for a better future includes making it easier for others to grow seaweed, which absorbs five times more carbon than land-based plants. In his new book, Eat Like a Fish, the ocean farmer writes: This generation’s “go west, young man” is “head out to sea.”(Photo source: Matthew Novak)

Bren Smith is what’s known as a restorative ocean farmer. Instead of fishing for tuna and salmon, he grows kelp and shellfish in the Long Island Sound using an innovative method of vertical underwater farming. But he got his start in commercial fishing, finding a dangerous sort of salvation at sea and learning grim truths about the fishing industry that feeds America’s fast-food obsession. His book, Eat Like a Fish, is the story of his “search for meaningful work” – and a meaningful life – at sea. It’s also a story about combating climate change.

Regenerative fisherman Bren Smith, makes a compelling case for establishing underwater farms in his first book, Eat Like a Fish.

Right from the start, Smith gives us the nitty-gritty on why we need this book, why we need to farm the sea, and how to make it happen. He tells us that seaweed absorbs five times more carbon than land-based plants, and oysters filter nitrogen from up to fifty gallons of water a day. This generation’s “go west, young man,” says Smith, is “head out to sea.”

Eat Like a Fish is a tale of maritime thrills, drug abuse, love, salvation, and adventure. It’s unexpectedly exciting for an educational book about farming. Smith grounds his narrative by splicing in chapters on ocean farming that offer shockingly simple and affordable instructions for starting, seeding, and harvesting an underwater farm. He makes it sound so easy, I briefly considered picking up and renting a plot of ocean.

Smith admits he struggled to write this book, having lost pieces of the narrative to drugs and concussions, but he has an undeniable knack for storytelling. He tracks his evolution from a childhood of survival on the rocky, Newfoundland coast, through his long career at sea.

It’s a story propelled by hunger. The paltry offerings of the Newfoundland soil: a pot of cabbage, turnips, and potatoes, occasional wild chanterelles, fire-roasted squid, freezer-burned meat shipped across the country, and the thrill of his first fast food meal. You can smell sea salt, acrid chewing tobacco, the briny liquor of fresh oysters, and the ripe stink of muddy boots.

Though he insists he feels out of place among foodies, he ties the narrative together with vivid descriptions of the smells and tastes of the sea. He tastes a sweet barbecue kelp dish, deep-fried tempura kelp, blanched kelp whipped intro froths of butter, and smeared on crostini. The liquor of his oysters “clear and sharp, hit the palate with the full force of brine, finished by a minor chord of sweetness.”

Seaweed promotes a healthier ecosystem and is highly versatile; it can be used as a fertilizer, animal feed, and biofuel. (Photo Source: Unsplash)

He also shares the gruesome practices that feed our growing fast-food obsession. Global conglomerates raze the ocean floor and dump dead bycatch back into the ocean. Nets left in the ocean can continue to kill marine life for centuries.

Californian squid is sent to processing plants in Asia and then sent back across the Pacific for consumption. One in three fish caught across the globe is never consumed, either left to rot or thrown overboard. It takes ten pounds of wild fish to grow one pound of farmed salmon.

After years working in an industry that pillages rather than farms the ocean, Smith eventually asked himself how we could do better. Today, his farm is essentially a storm-surge protector and artificial reef that feeds and protects his community. His crops need no freshwater, no fertilizers, and no feed. All it took was $20,000, twenty acres, and a boat.

Bren Smith’s goal in Eat Like a Fish is to get Americans to open our eyes to the dangers of the current food system and open our palates to new flavors. He extols the virtues and variety of sea vegetables, like sugar kelp or Irish moss, but admits to a “rocky romance” with sea greens. He wants Americans to do what he did and learn to love something new – something most Americans might consider gross and slimy. The title Eat Like a Fish, comes from the fact that most of fish’s nutritional value actually comes from their food: seaweed.

“We’ve got to move ocean veggies to the center of the plate, and that means convincing Americans that sea vegetables are no different from any other vegetable,” he writes.

“It’s frustrating to know that we could live in a world where seaweed replaces fossil fuels, but we don’t—at least not yet.”

Smith thinks seaweed can become the “new kale.” Seaweed is not only nutritious, packed with omega-3 fatty acids, vitamin-C, and protein, but it is easy to grow and incredibly sustainable. Still, kale had a rapid rise in success largely as a result of guerilla marketing schemes, and we have not yet seen the same kind of support for kelp.

Smith is not deterred. He sees many roles for seaweed beyond filling up our plates with kelp noodles. Kelp and shellfish can be used for “pollution farming,” that is, pulling pollutants from bodies of water, notably the Bronx River. He also sees kelp as an alternative to soy, which is woven into a huge number of industries, and wreaking havoc on the environment and public health.

Seaweed, just as versatile as soy, can be used as a fertilizer, animal feed (it has been found to reduce methane production from cows by 99 percent), and biofuel (it can yield up to 50 times more energy per acre than land crops). And it’s safe.

Smith harvests oysters from his Thimble Island Ocean Farm off Branford, Connecticut. (Photo Source: Ronald Gautreau Jr.)

Soy production, on the other hand, destroys natural ecosystems, causes soil erosion, and uses massive quantities of pesticides, herbicides, and fertilizers. In 2013, researchers found three times the allowable levels of Roundup in soy, but instead of excoriating Monsanto, the EPA tripled the allowable limit of the toxic herbicide.

To make it easier to realize the dream of more seaweed for all, Smith has created a program called Green Wave that gives new farmers the know-how to grow it. For Smith, climate change is not an “environmental issue” but a matter of “bread-and-butter economics” for working-class Americans. For someone whose livelihood can be ruined by a hurricane or sea acidification, global warming is personal.

He understands the time for small actions is over, but he’s not a fan of Big Ag—even at sea. Big Ag is rarely low impact, with huge, ugly structures, and a tendency toward harmful monoculture. Instead he promotes building a huge network of small, accessible blue-green farms.

There is plenty of room for small farmers, he writes. In fact, sea farming is inherently more fair and open than farming land. Anyone can boat, fish, or swim on rented plots of water, because the jurisdiction is limited to the right to grow, but not the right to own or privatize an area of ocean. Smith thinks of himself as a park ranger of the ocean, building community support and “protecting, not privatizing” ocean spaces.

In the course of reading this book, I found myself daydreaming about Smith’s vision of bivalves and sea greens transforming the world. Maybe it’s idyllic, but it’s also necessary. Too often we read about the destructive forces of our agricultural system, without being offered a constructive vision for a better world.

Oysters can filter nitrogen from up to 50 gallons of water a day. In Eat Like a Fish, Smith offers step-by-step instructions to build a restorative ocean farm. (Photo Source: Unsplash)

The very basis of American agriculture is tapping into existing markets, producing what we already like to eat in massive quantities, and destroying the earth along the way. Smith asks us to move with the earth instead of against it, and bend to the ocean’s will. He is suggesting something radical: changing our tastes.

Eat Like a Fish is most powerful when it asks us to consider what makes our lives meaningful, and what we are willing to change.

Is it really so simple to save the planet? It’s frustrating to know that we could live in a world where seaweed replaces fossil fuels, but we don’t—at least not yet. And Eat Like a Fish made me want to do something about it.